D-Day, Sydney Stadium.

D-Day, Sydney Stadium.

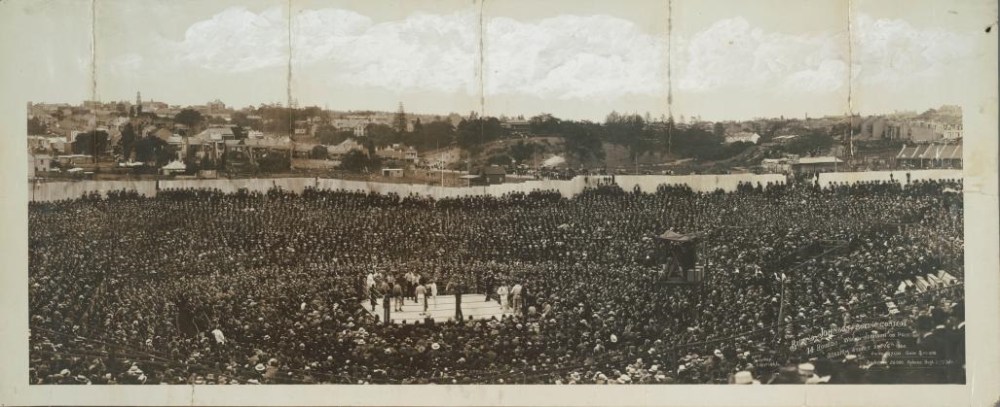

Boxing Day 1908 dawned overcast and mild in Sydney but the air was filled with an almost palpable excitement. All roads led to Rushcutters Bay and the former market gardens transformed into an open air boxing arena through the force of H.D McIntosh’s will. Since Christmas night, Sydney Stadium was descended upon by eager fans, transported by car, carriage, and horseback, all prepared to brave the elements overnight in readiness for the big fight.

By 10am, an hour before the fight was scheduled to start, each and every seat inside the stadium had been claimed and the largest crowd in boxing history to that time was officially in attendance. Despite the vast sea of people being at fever pitch for the big fight, Jack London made special note of its good nature. “The spirit of the stadium crowd inside and out with its fair-minded and sporting squareness was a joy to behold,” he wrote post fight in the New York Herald. “Never in my life have I seen a finer, fairer, and more orderly ringside crowd.”

With ring-side seats at £10 a piece, and with an estimated 20,000 excited fans in attendance, Hugh McIntosh’s gamble was a resounding success with gate takings a world record £26,000. There was one last negotiation for Huge Deal to navigate before the contest took place, when – having seen the size of the crowd in attendance – the challenger demanded a bigger cut of the pie or he would not fight.

Not in the mood for arbitration, McIntosh took an extremely strong arm approach to his last minute discussions with Johnson. Grabbing a revolver, he burst into his dressing room. “If you’re not in the ring in two minutes,” he snarled, “I’ll blow your brains all over the floor.” Johnson rose with alacrity, his gold teeth flashing as he grinned, “Massa Mac, Ah’m on mah way.” Just like that, the pieces were all set in place and Jack Johnson, Tommy Burns and Hugh McIntosh had their date with destiny.

The Fight

The Fight

The fight. The word is a misnomer. There was no fight. No Armenian massacre would compare with the hopeless slaughter that took place in the Stadium.

Jack London – New York Herald

Fresh off his last minute ‘negotiations’ with McIntosh, the Giant Texan was the first man to the ring, all confident smiles and sculpted muscle. The Champion followed him moments later to the sound of rapturous applause, his status as crowd favourite in no doubt. Despite the unquestioned support, London described his appearance as “pale and sallow, as if he had not slept all night, or as if he had just pulled through a bout with fever.”

The folly of those wagering on the fight, through whose weight of money had made Burns favourite, was now painfully obvious. Not only did Burns look “pale and sallow”, some even suggested in the weeks, months and years that followed that he was suffering through a bout of influenza at the time of the bout, but the physical advantages enjoyed by the challenger were on show too.

Bigger, stronger and faster, Johnson went to work early on the champion and put him down twice in the first round to the dismay of the large crowd. Despite racially charged abuse directed loudly and constantly at him, the challenger toyed with Burns. Standing 18cm taller and 11 kg heavier, Johnson would at times allow Burns to land blows to his body such was his confidence in victory.

“Cahm on leedle Tahmmy,” Johnson would needle the champion as he opened his body to Burns’ blows. Having received the best the Canadian could offer, Johnson would strike back with the type of sledging the Australian Cricket Team would be proud of. “What’s wrong Tahmmy? You hit like a girl,” he would gleefully taunt Burns, with his golden toothed smile almost as painful at these times as his ruthlessly efficient body blows.

Over a century later, the footage of the fight illustrates the theatrical way in which Johnson went about his business. Throughout the bout his confidence was on full show as he smiled, preened and posed to the dismay of the crowd and to the torment of his opponent.

From the opening moments of the fight, the result was never in any real doubt nor was the courage of the champion. Despite being so horribly overmatched and so completely dominated, he never once backed down from the challenge and continued his futile efforts to retain his belt. It was this bravery, along with Johnson’s desire to deliver as much punishment as possible that saw the fight last until the 14th round. At numerous stages, Johnson would prevent the champion hitting the mat and hold a clinch to allow him time to recover so that the carnage could continue as long as possible.

London, writing of the fight, was critical of this approach by Johnson. “One criticism, and only one, can be passed upon Johnson. In the thirteenth round he made the mistake of his life. He should have put Burns out. He could have put him out. It would have been child’s play. Instead of which he smiled, and deliberately let Burns live until the gong sounded,” he wrote.

This ‘mistake’ was not at all costly, with the fight brought to an end in the very next round when police intervened to end Burns’ punishment. While it might have robbed Johnson of the chance to put Burns to the mat once and for all, it also brought to a successful end his relentless chase of the World Heavyweight title. Without question the better man on this day, it did not stop some racial based cries for a challenger to win back the title for the Caucasian race and to claim the belt from the new champion.

The Search for ‘The Great White Hope’.

You paid and cheered and you hooted, and this is your need of disgrace;

It was not Burns that was beaten – for the nigger had smacked your face.

Take heed – I am tired of writing – but O my people, take heed,

For the time may be near for the mating of the Black and the White to breed.

Henry Lawson in response to Johnson v Burns

London was the first to make the demands for a white champion to regain the title. “But one thing now remains. Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you! The White Man must be rescued,” he concluded his coverage of the bout in the New York Herald.

Jeffries, who had refused to offer Johnson a shot at the title when champion, answered the call and finally faced Johnson in the ring . Two years after the Texan had brutally acquired the title in Sydney, he defended it against Jeffries in a bout declared with no end of hyperbole as the ‘fight of the century’.

I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.

Jim Jeffries before the fight

Just 15 rounds into the scheduled 45 round ‘super-fight’, rather than prove his stated aim, Jeffries had instead demonstrated the shrewdness in having avoiding Johnson’s challenge for as long as he had. After suffering a frightful beating, bruised and battered, he was knocked off his feet for the first time in his storied career. After only narrowly avoiding being counted out he was quickly returned to the canvas twice before his corner threw in the towel to admit defeat.

It would be the fifth of ten defences of his title that Johnson would make in an almost seven-year reign as World Heavyweight Champion. The curtain would be drawn on his time as champion in a controversial defeat to Jess Willard in Havana in 1915. Under the April Cuban sun, a wilting Johnson was knocked out in the 26th round of a scheduled 45. Rumours would circulate in the years that followed that Johnson had taken a dive, claims that Willard would not refute but express frustration at for a surprising reason. “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there,” he would answer when asked about the controversy surrounding his victory.

Johnson would never again be in a position to contest the world title but would continue fighting well into his sixties. The one-time champion taking part in two exhibition bouts in November 1945 at the age of 67. He may well have continued into his seventies too if not for his untimely end as a result of a car accident in 1946. Having faced countless challenges inside and outside the ring, it was a sad and abrupt end to a life lived large and loud.

Posthumous recognition.

A controversial figure in life, the recognition of his achievements came mostly after his untimely death. The man widely considered the greatest boxer, Muhammad Ali spoke often about the influence Johnson had on his life and career. An inaugural inductee into Ring Magazine’s Boxing Hall of Fame, Johnson received the same honour from the International Boxing Hall of Fame on its inception in 1989. The Galveston Giant was also belatedly celebrated by his home town, with a park named in his honour complete with a larger than life statue unveiled in 2012.

A forgotten champ.

A forgotten champ.

In the century and a bit since he surrendered his crown, the achievements of Tommy Burns have been mainly forgotten too. The Canadian’s place in history mostly now as a footnote in Jack Johnson’s historical tale.

Unfairly considered by some an invalid champion due to his claiming of a vacant title, Burns reign atop the heavyweight world is mostly disregarded by many historians. This is a disservice on many levels but not least of which being its indifference to his efforts to take the Heavyweight Title to the world.

A fighting champion, Burns defended his title more often than any of his predecessors and was the first to do so outside of the continental United States. In his three and half year reign, he would take the belt to England, Ireland, France and fatefully Australia. All of this while compiling a highly enviable record as champion. His record of eleven consecutive successful defences has only been bettered by three men, his feat of winning eight consecutive defences by knockout equalled once but never bettered.

A shrewd businessman, as evident in his world record payday for his fight with Johnson, Burns built a large fortune post boxing before the Great Depression eroded much of the business empire he had built. He would spend much of his life afterwards as a door to door salesman and security guard before becoming an ordained minister late in life. In 1948 at 73 years of age, while visiting a friend in the church, a heart attack would bring an end to the life of the only Canadian born Heavyweight Champion of the World.

He would be honoured by Ring Magazine with induction into their Hall of Fame six years after Johnson, it would be the same length of time after his old foe’s induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame that he would receive the same honour. While largely forgotten at the time of his death with just four people in attendance at his burial in an unmarked paupers gave, a fund raising effort has seen this rectified. He has also since been recognised with a plaque in his hometown of Hanover in the North East corner of Town Park.

Huge Deal McIntosh and his ‘Old Tin Shed’

Huge Deal McIntosh and his ‘Old Tin Shed’

What of the man who profited most from the successful crossing of the coloured line? Until his death, broke and penniless in 1942, Hugh McIntosh would continue to display the same entrepreneurial zeal that made the Johnson v Burns fight possible in the first place. With wildly varying degrees of success, McIntosh would continue to stage prize fights, make a foray into music theatre, took ownership of the oldest newspaper in Sydney, and tried his luck abroad with multiple business ventures in the UK.

Never in the history of showbiz, in any major city anywhere in the whole wide world has there ever been anything like it for a big night venue — whether it be a world championship boxing stoush, dwarf wrestling, roller derbies, religious revivals, pop and jazz concerts … you name it. The Stadium … was just something else. It was uniquely Oz. Uniquely Sydney. Nowhere else was there or could there have been a joint like the Old Tin Shed.

John Byrell

The ‘tin shed’ he built to stage the momentous fight would prove to be the longest standing of his achievements. He would quickly add a roof to the primitive structure, with the concrete foundations required for its addition entirely transforming the look and feel of the venue. With the arena now protected from the elements, it became an all-purpose all-weather venue and a much loved part of Sydney’s sport and music scene. Until its demolition in 1970 to make way for the construction of the Eastern Suburbs railway, the Stadium welcomed the likes of The  Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Little Richard and Chuck Berry in between countless boxing and wrestling matches.

Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Little Richard and Chuck Berry in between countless boxing and wrestling matches.

Where once the eyes of the world turned expectantly for the biggest prize fight ever fought on these shores, its location is now marked by a modest imminently missable plaque in a nondescript suburban park obscured from passing traffic by a shrubbery. Where once seemingly all of Sydney rushed for one of the most memorable moments in sporting history, their descendants pass hurriedly without a second glance. Despite this, and the passing of more than a century, the tales from Boxing Day 1908 live on as important today as they were when the events occurred.

Enjoyed our Flashback Friday look back at Burns v Johnson? Be sure to check out more of our Flashback Friday collection here. If you really like it, could you do us a favour and like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

One Comment Add yours